Regrets Only

Rule breaking, wedding planning, and the people we might've been.

When I got engaged, I discovered it was a good way to collect unsolicited opinions — about love, about marriage, but mostly, about weddings.

Whenever anyone asks after our plans, I am quick to joke that you’ve never met two people less interested in a wedding. (I hate planning; he hates attention. This does not an epic fete make.) But this is often met with looks of confusion and concern.

“But you need to have a party,” says everyone, as though it’s mandated by law.

“You should at least go somewhere!” says a friend, to the suggestion of City Hall.

“No no, you can’t go away,” says another, at the mention of an elopement. “I need to be there!”

“The profound thing about a wedding is that you share it with everyone,” says one acquaintance who, ten years onward, is still dissecting the amount of personal drama that went down at hers.

Occasionally, I’ll hear, “Oh, that’s wise,” or “Good for you!” followed by a tale of what they wish they’d done differently.

The most impassioned reactions often spring forth from people I’d never expect. (Our families have been commendably chill; it’s everyone else that has feelings.) In all cases, I suspect their suggestions are attempts to justify or rectify their own experiences, the choices they did (or didn’t) make.

Earlier this week, a friend sent me a link to this New Yorker piece, seductively titled, “What if You Could Do It All Over?” We’d both read it when it first published, in the thick of the pandemic, but the algorithm had unearthed it once again. As I read, familiarity washed over me with every paragraph. I immediately shared it with two more friends who had voiced concern over choices in recent days. It seems there are a bunch of us perpetually dodging regret.

It’s a worthy read, but as paywalls and time are realities, here are a couple quotes that stayed with me:

“We all begin with the natural equipment to live a thousand kinds of life but end having lived only one.”

“We have unlived lives for all sorts of reasons: because we make choices; because society constrains us; because events force our hand; most of all, because we are singular individuals, becoming more so with time… For some people, imagining unlived lives is torture, even a gateway to crisis.”

Wondering after possibilities is a common, perhaps inescapable, occurrence. The more days we live, the more paths unfurl behind us, rippling in our wake. What if we’d taken that chance? What if we’d quit sooner? What if we’d held on a little tighter to the one that got away? What if…

As a practice, it’s about as useful as imagining how life might look if we’d been born into different circumstances, different bodies, different eras. It makes for compelling fiction, rich but regrettable, without much hope of bettering our reality.

As the essay posits, “Part of the work of being a modern person seems to be dreaming of alternate lives in which you don’t have to dream of alternate lives.” Like an M.C. Escher sketch, where one option leads to another, and all of them leave us wondering.

Here’s something I wish someone had told me when I was younger: There are no rules.

Or rather, there are an awful lot of rules. Infinite rules! Rules for days. But we only need to follow the ones that work for us.

I’m not talking about laws, of the legal or moral variety, which are typically in place for good reason. I’m talking about nonsensical societal guidelines, about wearing white after Labor Day or not dining out alone. While I’m all for rules as they relate to courtesy and awareness — if you leave your shopping cart in the middle of the aisle so that everyone else has to navigate around it, I am coming for you — I can say, without hesitation, that minding the rules has never led me where I want to go.

Growing up, I was taught to wear what is appropriate, a maxim that found me donning cardigans and blazers and skirts of a modest length.

In my early twenties, I worked in fashion, which offered a distinct set of guidelines. I was told to dress up — way up — so that at worst, everyone had something interesting to look at!

Later in my career, a successful acquaintance shared their personal philosophy to deliberately dress down for important meetings, something they considered a “power move.”

The point is, if you consult as many sources, you’ll find just as many philosophies for getting dressed. Or writing a book. Or throwing a party. Or raising a child. Or whatever it is we venture to attempt.

There are no rules, no one right way. How about that?

All throughout my twenties, as friends got married, I pined for a meaningful occasion of my own. I read more than a few books on the topic, gorgeous volumes about dresses and cakes and flowers and candles, which I pored over then stashed in my closet so no one would get the wrong idea. But life had other plans.

When I got engaged, I was a) thirty-seven years old, and b) completely okay with the idea of a life that might not include traditional marriage or partnership. By then, I’d been to big weddings and small weddings, witnessed nuptials in backyards and grand hotels and city halls with automated call systems that rival the DMV. I’d danced at a disco party celebrating signed divorce papers, along with a bevy of bachelorette bashes, sometimes for the bride’s second (or third) time. I’d seen cold feet and meltdowns and affairs so hasty they made Love is Blind look sensible. I had also beheld the kind of love — in many shapes and forms — that reaffirmed why anyone attempts a connection in the first place.

And all of it was beautiful.

Those books are long gone, donated many moves ago as I bounced from one solo apartment to the next. Where I once longed for an epic gown, I now dream of comfortable footwear and a dress I might wear again. Maybe some photos in front of the Krispy Krunchy Chicken where we parted following our first date.

My wants are not for everyone — not even for the person I used to be. But the thing about choices is they always come with context, bound by the fibers of experience and place and time. These are mine.

I occasionally find myself wondering about the projects I abandoned before they found success, the alternate paths that pointed somewhere else. In another life, I might’ve settled down sooner. Lived in a different place. Embodied some unrecognizable version of me.

But I always come back to the positives. As I type this: my dog’s warm body against my foot, the blossoms outside the window, the sound of a choir echoing from a nearby church. If you change one brick, everything around it shifts.

Maybe the reason I despise plans is because so many things — paths, pursuits, parties — almost never go according to one. As the days unfurl and the sliding doors close and I am left with the current sum of my choices, I defer to this truth: If I’d gotten everything I wanted, I wouldn’t have wound up with so much of what I love.

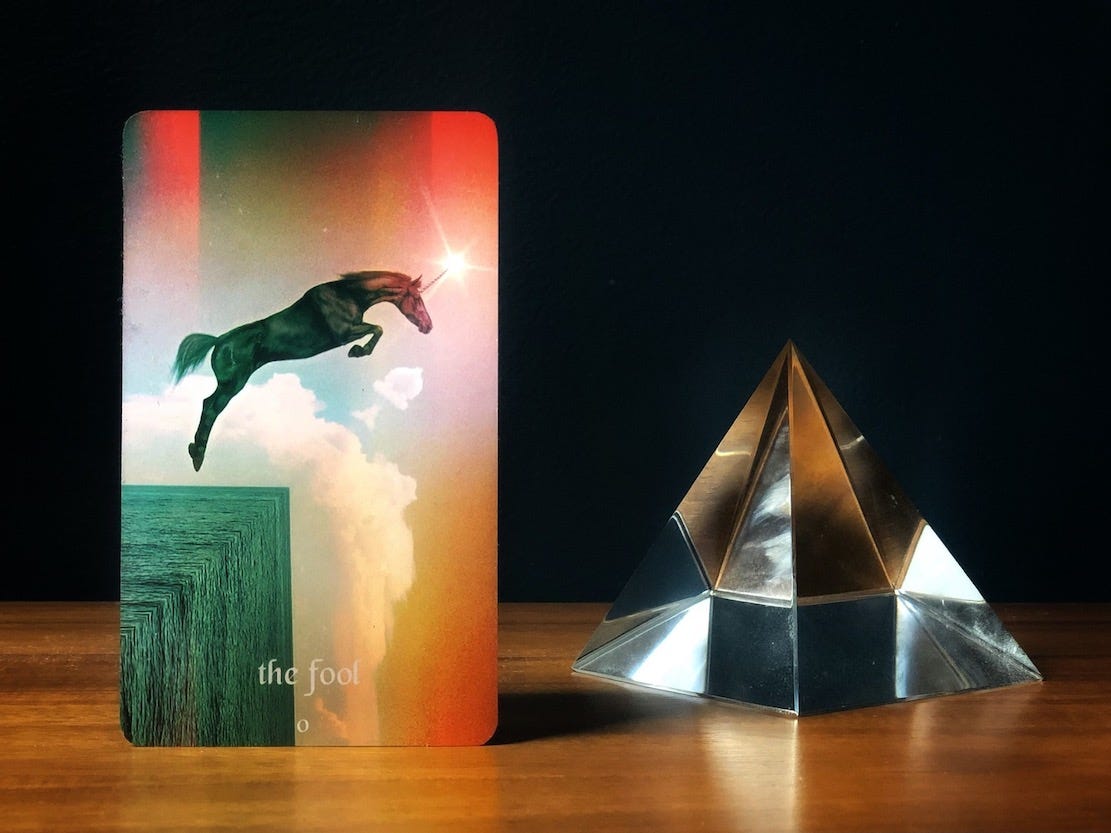

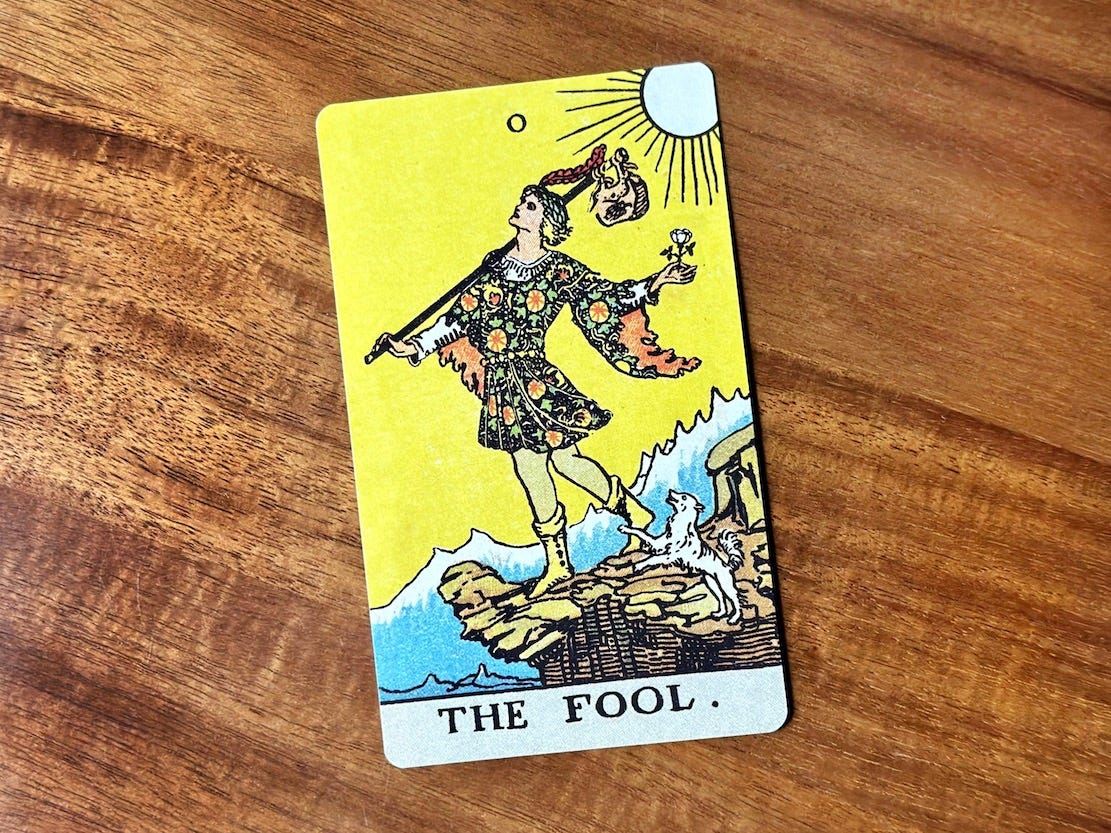

Card of the Week

Here is this week’s card for the collective, as well as some thoughts to carry into the days ahead. As most modern readers will tell you, the tarot is not about fortunetelling, nor is it about neat, definitive answers. The cards are simply one path to reflection, a way of better knowing ourselves and others through universal themes. If this reading resonates with you, great! And if not, no worries. Take whatever may be helpful and leave the rest.

The other day, I found myself walking behind a parent and child. “Maybe I’ll be a vet,” said the girl. “Or maybe I’ll be a people doctor. Or maybe I’ll be a scientist.” It sounded nice — a world full of possibilities. Like choosing fortunes from a hat.

It seemed especially compelling as I was feeling down this week, mired in worries and doubt. I was grateful when this card jumped out of the deck. One of my all-time favorites, The Fool radiates the beauty of being a beginner. It promises new paths, new outlooks, new opportunities.

There is a certain unstoppable quality inherent in those who are so new, so green as to believe anything is possible. On the one hand, they may be wildly off the mark. But they may also have the best chance of achieving it.

The Fool wants you to reconnect with that kernel of excitement you felt at the outset. Why did you take that first step, whether in love or career or creativity or crusade? What were you chasing? What feeling or change did you wish to bring about?

The very first card of the Major Arcana, The Fool bears the digit zero. Some may interpret it as worthless, while others see only a perfect circle, a value that cannot be quantified. This is the wisdom inherent in this card: When you have nothing to lose, you have everything to gain.

The Fool moves ahead, bound for the edge, without trepidation or fear. What will greet them on the other side? Will they fall or will they fly? The Fool suspects there may not be a difference.

From our cautious, human vantage point, this image may spark worries about the character’s fate. It mirrors the way we can look at our own life choices — our dreams, our fears, our secret longings — and barrel straight to the anticipated outcome, without giving them a chance to thrive.

What if it doesn’t work out? What if I get rejected? What if I fail? What if it’s difficult? What if, what if, what if…

This card asks: What if you didn’t worry so much about whether the book will sell, the date will go well, the idea will work… What if you let your excitement lead you, step by step, to something pure and fulfilling? What if you dare to focus on the pursuit, not the outcome? What if you replaced “What if?” with “Why not?”

In the days ahead, this card asks us to reclaim the energy, the enthusiasm, the belief that we once felt. What fills you with excitement? Think back to a time when you were first dreaming, anticipating, making plans. How did it feel?

How did you want to change the world before they said it couldn’t be done?

The Fool encourages all of us: Remember why you started. Wonder is its own compass, inexperience its own brand of wisdom. Beginnings are beautiful. And they happen every day.

"If I’d gotten everything I wanted, I wouldn’t have wound up with so much of what I love"

My God, woman, what a sentence! It makes perfect sense. Just... damn.

Thank you Caroline for yet another 'wise' piece. This dropped in my SS tray 'literally' as I said to myself at dawn this morning, "I really don't feel like meditating and journaling today" And, in an almost silent whisper 'someone' replied "that's really OK, they are your rules". I've been taking a short course online on forgiveness and so many of the themes you mention have bubbled in and out of the writing for the course, with 'regret' often shouting the loudest. And there were with your insights, grounding me with The Fool who's been calling me for a long time now to just jump! 💜